by Brigid Rowlings, LHI Communications Director

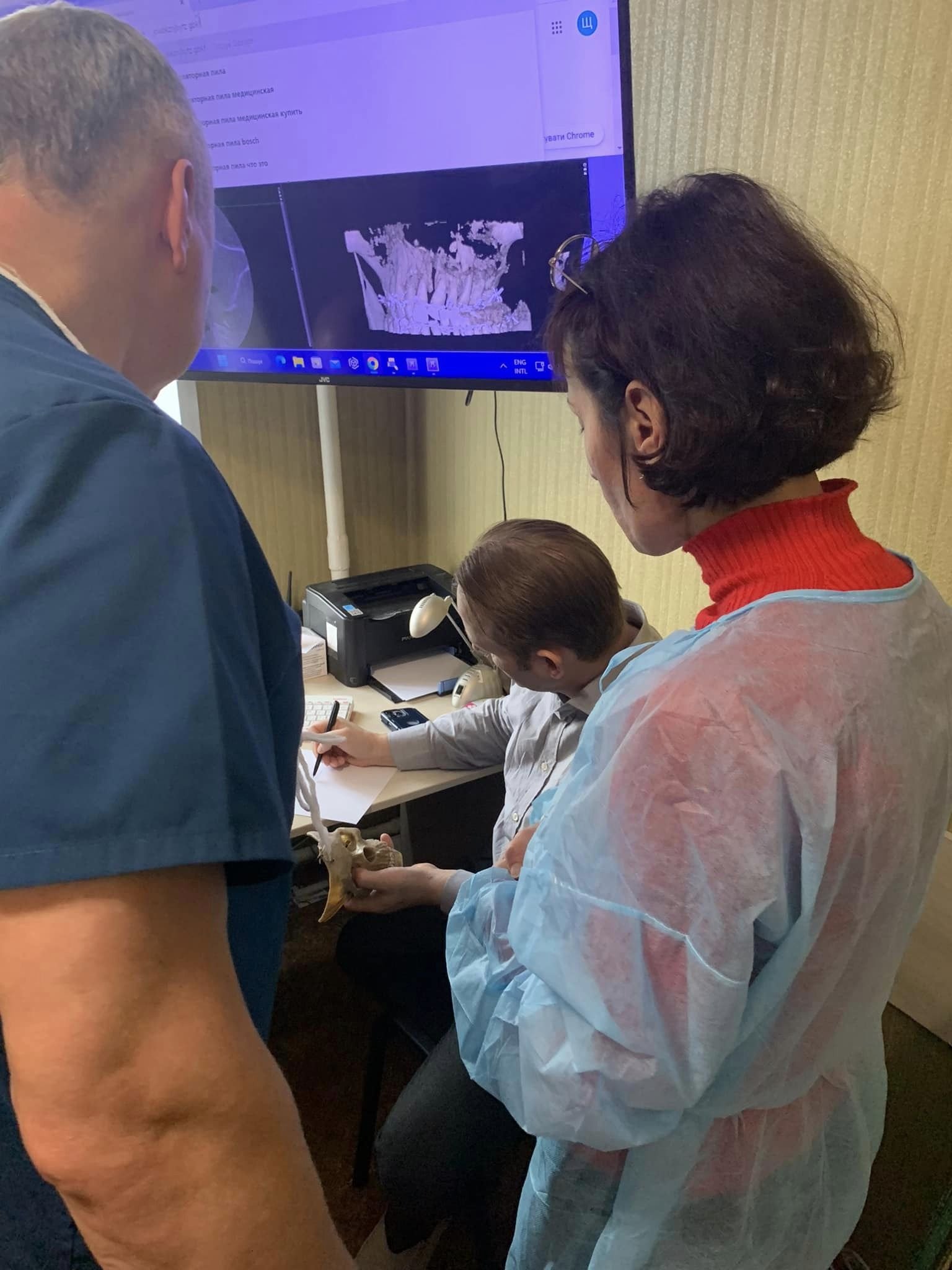

Dr. Aragon Ellwanger assesses a Ukrainian civilian badly injured by shrapnel.

How do civilians seek medical care when their country is at war? This question drew me up short. Hospitals must treat those injured by war, in addition to people who require urgent and long-term care for run-of-the-mill illnesses and injuries.

Battery powered incubators arrived from LHI to Ukrainian hospitals last month.

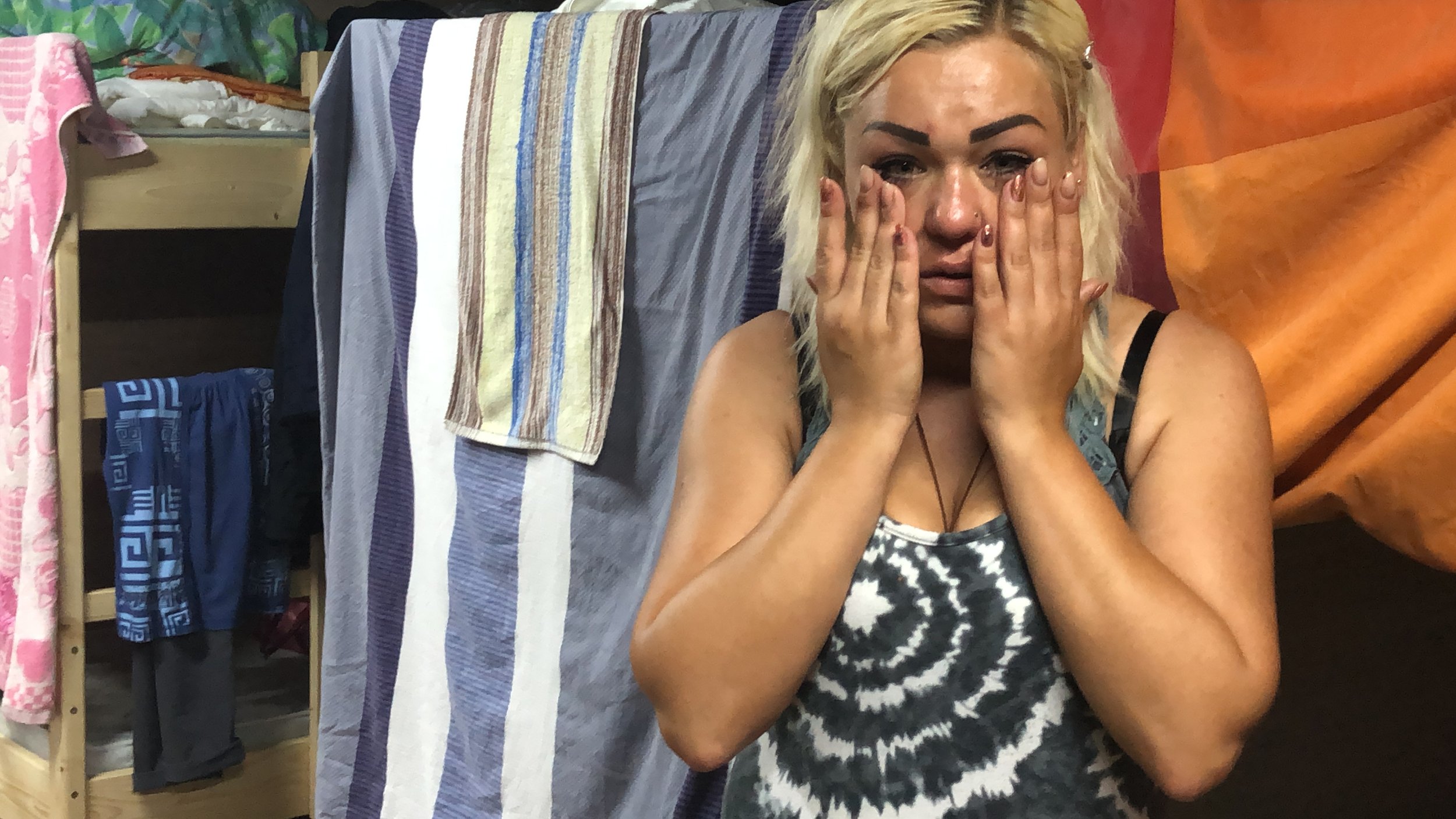

Babies

I had intense and unrelenting contractions when I was in labor with my son 10 years ago, and that was without power outages, supply shortages, and lack of heating that so many maternal wards experience in Ukraine. This is why LHI distributed battery-operated incubators to maternity hospitals and NICUs in Ukraine, with the help of Smart Aid. (Readers, remember that this is Brigid writing, not Hayley! Hayley does not have a secret child).

Health care workers at a surgical clinic near the front lines recently gave our Ukraine country director, Serhii, a tour of their clinic.

ICUs

Serhii, our Ukraine country director, recently visited a frontline surgical clinic in eastern Ukraine. He spoke with Anna, Director of Surgery, who left her job in Kyiv to care for cancer and ICU patients whose treatments were on hold while war injuries were rushing in. With Anna’s guidance and Serhii’s expert fact-finding skills, LHI, in cooperation with our friends at Dead Lawyers Society (yup, it’s a play on the movie Dead Poets Society) funded essential laparoscopic surgical equipment to help Anna and other doctors meet ICU patient needs.

Dr. Aragon Ellwanger considers how best to treat a civilian patient with a war-related injury.

Civilian war injuries

Face-altering shrapnel and bullet wounds are now commonplace injuries at frontline clinics. I recently talked with Britta Ellwanger from ForPEACE, who works day and night to help on the frontlines. Her brother Dr. Aragon Ellwanger, a United States Air Force trained oral maxillofacial surgeon with experience treating frontline trauma wounds, joined her in Ukraine to assess needs at a frontline hospital.

He immediately noticed a patient, Volodymyr, whose jaw had been severely damaged by shrapnel. Even after surgery at the local hospital, his jaw had been sewn shut for three months, and he had lost 40 pounds. This is because, well, "how to repair bone shredded by shrapnel" or "how to reconstruct jaws shattered by bullets" are not typical courses in medical school. Another factor in the less-than-ideal surgical outcomes is that a lot of the hospital’s surgical equipment was either outdated or not working

Dr. Ellwanger performed a corrective surgery to undo the first surgery and then reconstruct Volodymyr's jaw. Now he can open his mouth again, talk, eat food, etc. Volodymyr was lucky, however. Patients with severe trauma injuries across Ukraine have to wait months for any sort of treatment. In some cases, family and friends will raise at least $80,000 for a medical evacuation to Western Europe or the USA to receive treatment, but that is a rare case.

Training surgeons

The best solution is to train Ukrainian surgeons in oral maxillofacial wounds and to encourage hospitals to upgrade their equipment. Dr. Ellwanger has sourced a portable medical kit that he can take to frontline hospitals to train their surgeons to treat injuries unique to wartime.

LHI is partnering with forPeace to cover the cost of this surgical equipment. We are excited that this project centers around training Ukrainian doctors and building the capacity of the healthcare system in Ukraine. We also know that this project will offer hope to hundreds of Ukrainian patients who have suffered devastating injuries.

If you’d like to learn more about this mobile surgical training project, please click here