by Brigid Rowlings, LHI Communications Director

Our teams continue to pump flood water out of homes and businesses. Serhii (middle), LHI’s Ukraine country director, has coordinated a huge response.

There are two fundamental truths when it comes to refugee work:

No single organization can tackle a crisis alone.

Refugees and displaced people understand their own needs best.

When we combine these two truths, we arrive at one of LHI's signature approaches: Providing high-level operational expertise to our local teams.

Our Ukraine response is a perfect example of this. We've set up ten operating centers throughout the country that we run with our local teams, each of whom provides a myriad of services.

When Russian forces destroyed Kakhova Dam in the Kherson region of Ukraine, 545,000 acres of rich farmland and villages were flooded with water that quickly became toxic from decomposing wildlife, chemicals and floating explosives. People needed rescuing from flooded homes and taken to shelters. Many people needed medical attention, including treatment for hypothermia and shock.

The team at the LHI Operating Center in Kherson hunkering down in their basement during a shelling attack.

As it happens, one of our ten operating centers is located right in the heart of Kherson. Our Ukraine Country Director Serhii immediately called our team to see what we could do. Within a couple of hours, we were evacuating people from the floods by boat. And a few days later, we purchased an industrial-quality truck to pump toxic water out of flooded homes. Simply put, there is no way we could’ve done this on our own, without our team in Kherson.

The NGO Hub in Kyiv became an emergency response center.

Our response to the flood extended beyond our operating center in Kherson. For example:

The LHI Shelter in Lviv has taken in people displaced by the flooding.

Our partner forPeace organized a shipment of water filters to protect flood survivors from contaminated water.

We turned our NGO Hub in Kyiv into a coordination center and temporary aid collection point for response to the disaster.

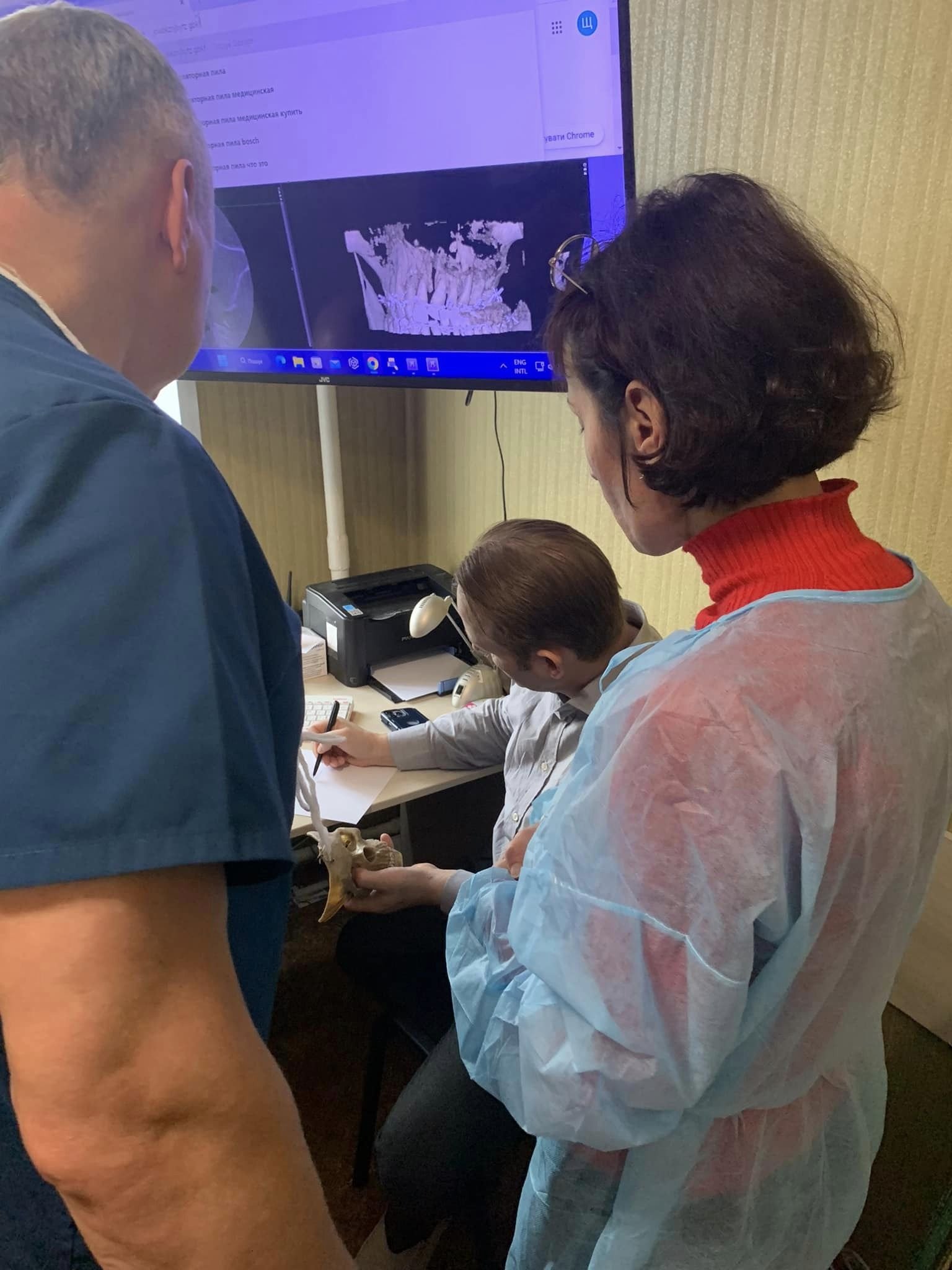

And, we were surprised to learn that a frontline hospital we’d supplied medical equipment to used those very supplies to treat flood victims who suffered hypothermia.

Our teams sourced boats and fuel to rescue people stranded in flood waters.

LHI's rapid, efficient, and effective response to the humanitarian emergency caused by the Kakhova Dam rupture was made possible through strong partnerships with local people and organizations.

Learn more about our commitment to empowering ordinary Ukrainians to assist their fellow citizens in need and support our cause by donating towards the purchase of essential items. Visit our Ukraine response page by clicking here.